While reviewing a paper a while ago, a single word in the methods section caught my eye: “randomized“. Based on that single word, I strongly suspected that the methods were not accurately reported and that the conclusions were entirely unsupported. But I also knew that I’d never be able to prove it without the data. Here, I’ll explain what happened in this one example of why empirical papers without open data (or an explicit reason why the data can’t be shared) hamper review and shouldn’t be trusted.

Starting the review

I got a review request for a paper that had been through a couple rounds of review already, but the previous reviewers were unavailable for the revision. I don’t mind these requests, as the previous rounds of review should have caught glaring problems or clarity issues. As I always do, I skimmed the abstract and gave the paper a quick glance to make sure I was qualified. Then I accepted.

While some people review a paper by reading it in order, and others start with the figures, I jump straight to the methods. The abstract and title made the paper’s goals clear, so I had a good gist of the core question. Since I tend to prioritize construct validity in my reviews, I wanted to know whether the experiment and analysis actually provide sufficient evidence to answer the question posed.

The methods

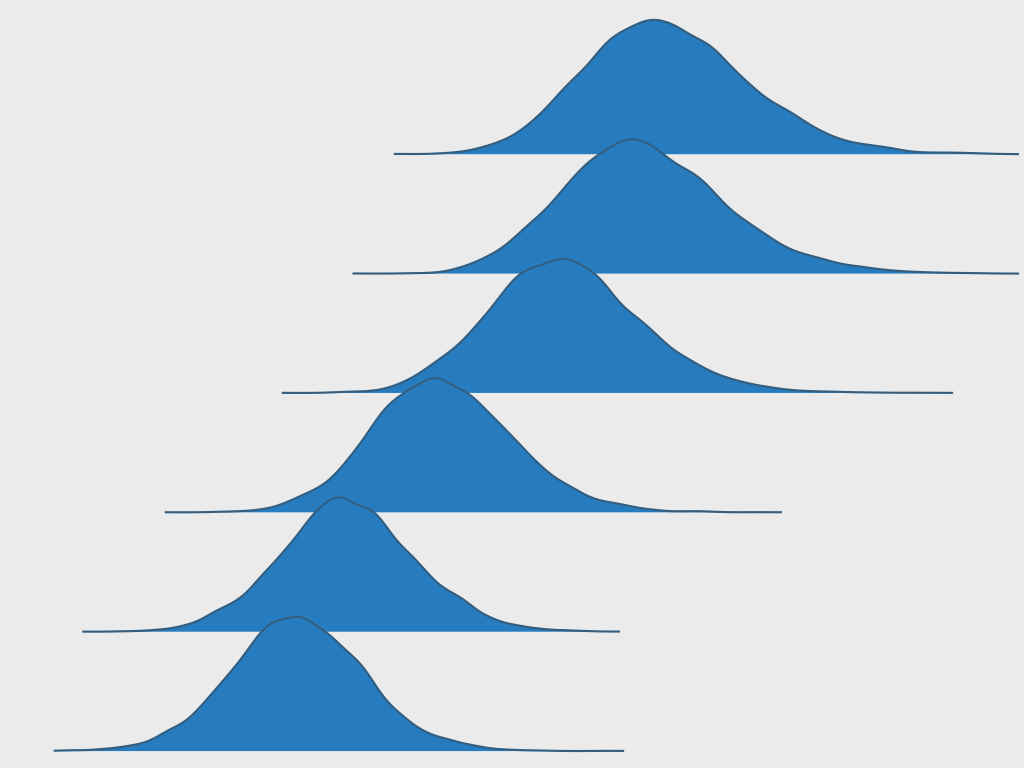

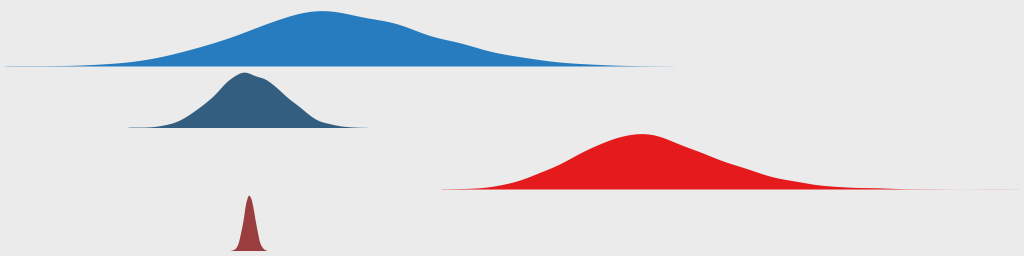

The experiment showed 4 different items, and the task was to select one based on the instruction’s criteria. Over 200 subjects were run. There’s no need to go into more specifics. It was a single-trial 4-alternative-forced-choice (4AFC) experiment that also had an attention check. The items were shown in a vertical column, and the paper noted that the order of the items was “randomized” and that an equal number of subjects were presented with each ordering. The goal was to figure out which item was more likely to be selected.

Did you spot what caught my attention?

Continue reading →